By Alan Williams, President, The Williams Group

(References at the bottom of the page)

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Objective

Executive Summary

The Procurement Process

Schedule

The US Navy’s FFG(X) Competition

Weight Risks

Technical Risks

Conclusion

Recommendations

OBJECTIVE

The objective of this paper is to provide a critical examination of the estimated life-cycle costs of Canada’s Canadian Surface Combatants, to provide some insight and understanding as to the key cost drivers, and to present some recommendations on the way forward.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Between $213.5 and $219.6 billion dollars. This is the estimated price tag to acquire, operate and support the Canadian Surface Combatants throughout their life-cycle of approximately 30 years. Approximately two-thirds of these costs are attributable to the long-term operations and support (O&S) costs of the CSC. This figure does not include another $19 billion dollars due to needless and unnecessarily lengthy schedule delays. Compared to a similar acquisition by the US Navy (The FFG(X) program) the CSC program will take over three times as long for our Navy to receive its first ship and will cost Canadians nearly three times as much per ship.

While shocking in its magnitude, these costs were predictable from the moment the ill-conceived procurement process to acquire these ships was announced. What else could one expect from a process:

1. Where the federal government chose to abdicate its responsibility to acquire goods and services on behalf of the taxpayer and to offload the accountability to the private sector;

2. Where core procurement principles of openness, fairness and transparency are replaced by practices that are of restrictive, biased and opaque;

3. Where the federal government can require bidders to summarily transfer their Intellectual Property to potential competitors; and

4. Where taking more than a decade to acquire a single (first) ship is deemed acceptable.

Seven different cost factors were examined to determine the total costs for the CSC. Three of these factors - the pre-production costs, the production costs and the project-wide costs were extracted from the 2019 update on the costs of the CSC produced by the Office of the Parliamentary Budgetary Officer (PBO)[1]. These cost estimates were developed by the PBO using costing software and then compared to alternative heuristic methods. It is excellent work and there is no reason to second-guess its results. The PBO is currently working to update these costs. To the extent that they are changed, so too will these cost estimates in this paper need to be modified. In addition to these costs, this paper examines the cost impact of four further factors - the long-term O&S costs and the potential costs due to risks involving schedule delays, weight increases and technical issues.

Table 1 below summarizes these expected costs (in $ billions).

Finally, there are legitimate concerns that some of the systems and weapons chosen for the CSC may not provide the capability to undertake the missions required of the Navy. These are detailed below and need to be addressed immediately.

THE PROCUREMENT PROCESS

To be efficient and effective, a defence procurement process needs to adhere to these fundamental accountabilities:

· The military - to develop its statement of requirements (SOR);

· The government’s departmental officials - to undertake an open, fair and transparent process designed to meet the military requirements and to recommend a winning supplier to the government;

· The defence industry - to organize itself into appropriate consortia to best meet a Request for Proposals including the military’s requirements and to submit their bids in a timely fashion;

· The elected officials - to authorize the start of the procurement process and to accept or reject the recommendation from their officials.

Unfortunately, by deviating from these basic accountabilities in two fundamental ways, the government undermined the integrity of the process and contributed to the ever-escalating costs for these ships. First, by selecting Irving Shipyards Inc. (ISI) as the designated shipyard, the federal government forced all potential ship designers and system integrators to work with ISI. By doing so, the government interfered with industry’s ability to self-select its partners to best respond to the military’s needs.

Governments must often balance multiple priorities that can conflict with each other. In this instance, in June 2010, when the government released its National Shipbuilding Procurement Strategy (NSPS), it was trying to address the historical “boom and bust” in naval procurement in Canada. With respect to the construction of large ships greater than 1,000 tonnes, the Government decided that the best way to ensure the stability of its shipbuilding industry was to select two shipyards, one to build combat ships and one to build non-combat ships. In September 2010, the Government issued a Statement of Interest and Qualification (SOIQ), launching the competitive process to select these two shipyards. In February 2012, the federal government signed an umbrella agreement with ISI to construct Canada’s combat fleets including the CSC.

Whether this strategy will achieve its long-term objective is still to be determined. What is clear is that in the short-term, the 2010 strategy to acquire the CSC has led to an extraordinarily lengthy timeframe and to unacceptably high costs. As an alternative strategy, the government could have, and should have, run the CSC competition allowing industry to team with any Canadian shipyard, with the stipulation that the shipyard of the winning bidder would be entitled to the future construction of large combat ships. Such a strategy would have reduced acquisition time and maximized competition.

Second, it is completely unprecedented in any federal government procurement, let alone one entailing tens of billions of dollars, for the federal government to abdicate its accountability by largely offloading key decision-making authority to the private sector. Nevertheless, in January 2015 the Government compounded its distortion of the procurement process by announcing that ISI had been named the prime contractor for the CSC program. The role of the lead contractor effectively gave ISI overall control of the project. ISI would determine which companies would receive billions of dollars to develop, install and integrate the mission-critical systems into Canada’s fleet of surface combat vessels. This kind of abnegation of responsibility is comparable to the Government allowing a Canadian chartered bank to decide fiscal policy.

In October 2018, the group led by Lockheed Martin Canada (LMC) and BAE Systems, offering the Type 26, was selected by ISI as the preferred design team. In February 2019, nearly nine years after the process was launched, a contract was entered into with LMC for $185 million for the design portion of the contract. In many respects, this decision was predictable. LMC had successfully worked with ISI previously on the Halifax-class modernization program and ISI had confidence that LMC could deliver the goods. With billions of dollars at stake why would ISI take a chance with another company? However, what is best for ISI is not necessarily what is best for the Navy, for industry or for the taxpayer. No doubt potential bidders shied away from participating in the competition knowing full well the playing field was not level. The more limited the competition the more likely costs rise, forcing DND to allocate more funds from their limited capital budget towards this program.

Since being chosen, the LMC team has been selecting the systems and weapons for the Type 26 platform. Had the federal government maintained authority and accountability over the selection of the systems and weapons, taxpayers could remain confident that these decisions would have been taken consistent with the basic principles of openness, fairness and transparency. After all, any proven deviations from these principles could result in costly legal penalties. Instead, without a window into these deliberations, it is impossible to know what decisions are being taken and why. Are there large, undisclosed costs in highly developmental solutions, chosen simply because of proprietary interest? We just don’t know.

Ironically, the inclusion of a “requirements reconciliation” phase in the process was, by definition, a recognition that the overall process was deficient. This phase provided a mechanism to allow for the switching out of systems that did not fully meet the Navy’s needs or where the cost or risk of certain systems was beyond what the Government/Navy were prepared to accept. A properly constructed and rigorous process should have already selected the right systems to fit the budget and to meet the Navy's needs. There would have been no need to revisit the results and to ensure that appropriate decisions were taken.

Perhaps, even more significantly, the requirements reconciliation phase apparently allows for a change to the military’s SOR. The SOR is the bedrock of the competitive process. In order to be compliant, all bidders had to submit proposals to meet the SOR. To select a winning bidder and then to change the SOR is inappropriate. Such an action undermines the integrity of the process and raises the risk of successful legal intervention.

Nevertheless, during the requirements reconciliation phase, a senior procurement official admitted that DND was “re-looking at some of the requirements” the Navy set for its warship[2]. This begs the question as to whether or not it was DND that was pressing for the change or whether DND was simply responding to what LMC were prepared to offer in terms of systems or sub-systems. The lack of transparency makes it difficult to know.

It was also disappointing that there appears to have been no strategy to support world leading and proven Canadian made subsystems. While virtually all of the largest Canadian defence companies are foreign subsidiaries, many have been in Canada for decades and have established best of class niche products which are engineered and manufactured in Canada. In the case of naval subsystems, some of these were developed in conjunction with the construction of the Halifax Class, were supported by Canadian tax dollars, and have enjoyed a healthy export market.

Instead of supporting Canada’s domestic defence industry, the Government appears to have completely disregarded its own policy of supporting Key Industrial Capabilities (KICs). In the government’s policy statement, under the heading of “Leading Competencies and Critical Industrial Services”, one of the so-called KICs is “Marine Ship-Borne Mission and Platform Systems”. As the policy states: “The KICs represent areas of emerging technology with the potential for rapid growth and significant opportunities, established capabilities where Canada is globally competitive, and areas where domestic capacity is essential to national security.”[3] Instead of specifying proven globally competitive Canadian-made subsystems on the CSC, the government allowed bidders to choose foreign suppliers who were encouraged under the rules to promise unprecedented levels of ITBs. It remains to be seen whether or not these ITB promises will materialize at the end of the day.

What are the implications of these choices? Since Canada will be operating the Halifax Class for another 20 years as the CSC comes on stream, sailors will have to be trained on both systems. There will have to be separate supply chains, and separate budgets for future system upgrades on the Halifax Class and the CSC. Canadian taxpayers typically have little interest in the details of how ships are built, but when foreign subsystems displace proven Canadian products most taxpayers would see this as illogical, unfair, short-sighted and counterproductive. This is yet another example of how a flawed defence procurement process, created by Government to allow it to step back from its proper role left critical decisions to the private sector. It produced a costly result for the Canadian taxpayer and did a disservice to Canadian industry.

SCHEDULE

Time is money. As the PBO indicated in their June 2019 update, every delay of a year raises the incremental costs by a projected $2.2 billion. As indicated above, the procurement process was launched in 2010. Today, a full decade later, we are still at least three years away from beginning the construction of the CSC. This timeline runs counter to previous directives from the Assistant Deputy Minister of Materiel in the Department of National Defence and the Vice Chief of the Defence Staff of the Canadian Armed Forces aimed at reducing protracted procurements. In 2003, military personnel and procurement staff were instructed to take no more that 48 months from the launch of a project to the signing of a contract for implementation.[4]

In essence, the military was given two years to finalize its statement of requirements. The civilian authorities in National Defence and Public Works and Government Services Canada, now Public Service and Procurement Canada (PSPC), were given an additional two years to enter into an implementation contract allowing the winning bidder to begin the delivery period. This was to be followed by a five-year delivery period. This standard was critical in the successful effort to reduce the acquisition time frame to nine years from a historical average of nearly sixteen years.[5] With respect to the CSC, it is likely to take about 30 months following the completion of the requirements reconciliation phase for the government to complete the design phase. If the requirements reconciliation phase concludes by the end of 2020, an implementation contract would be signed in mid 2023 - 12.67 years following issuance of the SOIQ and 8.67 years above the standard. This equates to $19 billion[6] in avoidable costs.

One of its assumptions in the June 2019 PBO report is that construction of the first ship would begin in FY 2023-2024. However, the CSC are to be built by ISI following their construction of eight Arctic and Offshore Patrol Ships (AOPS), six for the Navy and two for the Coast Guard.

The current schedule anticipates that the construction of AOPS five and six are to begin in 2021 and 2022.[7] With AOPS seven and eight still to be scheduled it is highly unlikely that the ISI will begin construction of the first CSC before April 2024. Attaching a probability factor of 75% for this one-year delay leads to a cost estimate of approximately $1.7 billion.

LONG-TERM O&S COSTS

The issue of long-term O&S costs for any major defence acquisition is a critical factor in the calculus of procurement costs. In July 2010, the government announced that it was prepared to purchase 65 F-35 jets for $9 billion, with up to another $9 billion for long-term O&S costs.[8] Anyone with a reasonable understanding of defence capital acquisition and support would know that long-term O&S costs are typically two to three times the purchase price and as such, these government figures made no sense. Over the next few years, more realistic cost estimates became public. In March 2011, the Office of the PBO forecast the costs at $29.3 billion.[9] In May 2012, an analysis by this author calculated the costs at $40-$45 billion.[10] Later that year KPMG presented its independent cost estimate at $45.8 billion. In all of these estimates, the long-term costs were in the range of two to three times the acquisition costs.

Today, a weapon system is essentially software - often millions of lines of code. This software is subject to bugs and is readily in need of updates - all prohibitively expensive. Along with the need for preventative and corrective maintenance, major repairs and overhauls, technical assistance and testing, it should not come as a surprise that long term O&S is the dominant cost in the life cycle of a weapon system. Chart 1 below presents a graph from the U.S. Defense Systems Management College’s Acquisition Guide. It suggests the ratio of long-term support to acquisition is 2.7. Applying this ratio to the PBO’s estimate of the production costs ($53.2 billion), yields a long-term O&S cost of $143.6 billion. Interestingly, in May 2012 the PBO made a presentation on the F-35 to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts. In this presentation, the PBO noted that this same chart is included in DND’s own costing manual. One can only speculate as to why DND did not utilize this information when publicly reporting on the costs of the F-35. Tragically, this misinformation continues today with respect to the CSC. In its June 21, 2019 response to the PBO report, DND claimed that the main difference between its costing and that of the PBO was due to taxes.[11] The PBO included taxes, DND did not. DND noted that it remained confident in its “estimate of $56 to $60 billion for the CSC project budget.” This estimate may be technically correct if the project budget excludes the long-term O&S costs. Nevertheless, it is grossly misleading. Taxpayers are entitled to know how much the CSC will cost to purchase and maintain. As indicated above, that figure is significantly higher.

THE US NAVY’S FFG(X)[12] COMPETITION[13]

The focus of the upcoming PBO study of the costs of building the CSC is to also include comparisons with building the French and Italian FREMMs and the Royal Navy’s Type 31. While those two programs are generally similar in terms of size and scope, a more instructive comparison can be found in the US Navy’s FFG(X) program. Based upon the Italian FREMM, the FFG(X) acquisition largely avoided the pitfalls inherent in the CSC acquisition process. While the length and weight of the FFG(X) (496 feet, 6713 tonnes) are comparable to those of the CSC (491 feet, 6900 tonnes), the FFG(X)’s significantly lower costs and reduced acquisition time are quite striking when juxtaposed with the CSC program.

The FFG(X) competition was launched in July 2017 after experience with the US Navy’s littoral combat ships (LCS) showed that those ships were too small, under-armed, and lacking in endurance to perform the duties they had been assigned. As the US Navy’s objective was to procure the first of 20 FFG(X) in FY2020, they recognized that there was insufficient time to allow for a completely new ship design. Consequently, the procurement strategy for the FFG(X) was to require a modified version of an existing ship design - an approach they called the parent-design approach. The parent design could be a U.S. ship design or a foreign ship design. It was anticipated that this approach would reduce the design time, design cost as well as the cost, schedule, and technical risk in building the ship. Charts 2 and 3 below outline the required capabilities demanded by the US Navy.

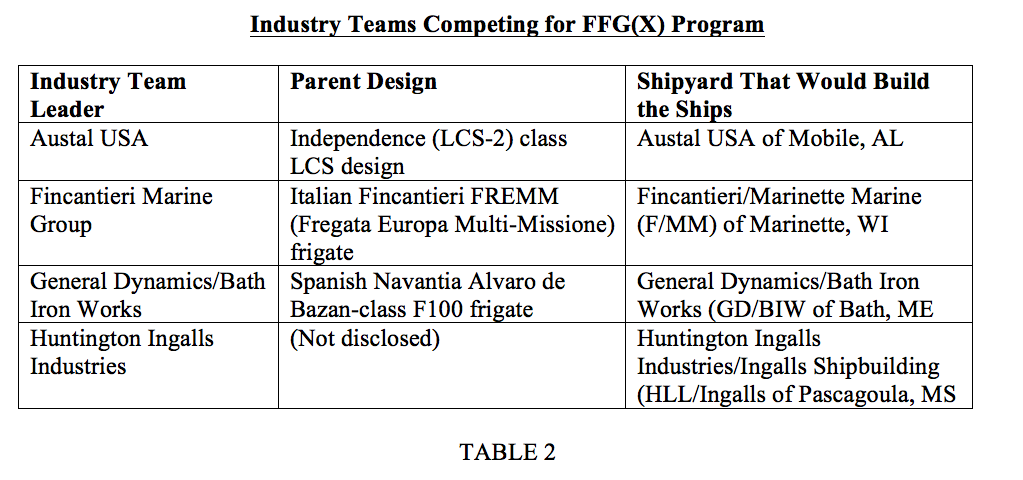

As shown in Table 2 below, four industry teams competed for the FFG(X) program. Two of the teams - one including Fincantieri/Marinette Marine (F/MM) of Marinette, WI, and another including General Dynamics/Bath Iron Works (GD/BIW) of Bath, ME - used European frigate designs as their parent design. A third team - a team including Austal USA of Mobile, AL—used the Navy’s Independence (LCS-2) class Littoral Combat Ship (LCS) design, which Austal USA currently builds, as its parent design. A fourth team—a team including Huntington Ingalls Industries/Ingalls Shipbuilding (HII/Ingalls) of Pascagoula, MS—did not disclose what parent design it used.

In April of this year, the US Navy announced that it had awarded the FFG(X) contract to the industry team led by Fincantieri for the first ten ships. Table 3 below reflects the funding and unit costs for the first nine of these ships. The bottom row converts these US costs into Canadian dollars.

In contrast to Canada’s approach to procuring the CSC, with respect to the FFG(X) the US allowed industry to determine how to best structure its partnering arrangements in order to bid. The US insisted upon off-the-shelf ship designs and systems. The net results are worth highlighting:

1. The US Navy issued its Request for Information (RFI) in July 2017 and is expected to receive its first ship no later than Sept 2021, a lapsed time of 50 months. In contrast, Canada issued its SOIQ in September 2010. As outlined above, Canada will likely not even see construction begin (not ship delivery) before June 2023, a total of 152 months—over three times as long as the US Navy!

2. By specifying the systems and weapons it required, the US Navy guaranteed they would obtain highly integrated, already-developed and shipborne-ready systems and weapons. Reducing these risks allowed for the shortened process time and lowered the costs. In Canada no such assurances exist.

3. It is noteworthy that BAE did propose a variant of the Type 26 to the Navy in 2017, but it did not receive one of the five initial developmental contracts in 2018.[15] Clearly, the US Navy did not consider the Type 26 an off-the-shelf design.

4. The average cost per ship for the nine FFG(X) is $1,284 million in Canadian dollars. In contrast, the average production cost for the 15 CSC is estimated at $3,546 million Canadian dollars - 2.76 times more expensive.

5. As the US Navy retained program authority, bidders did not risk sacrificing their Intellectual Property to a potential competitor.

WEIGHT RISKS

In its June 2019 update on the CSC costs, the PBO reported that a key cause of the cost increase from its 2017 report was due to the forecast weight increase between 2017 and 2019.[16] Further, in correspondence with this author, the Office of the PBO indicated that, “The increase in tonnage, compared to the other factors, is responsible for the largest proportion of the increase in cost between the ’17 and ’19 estimates.” In its 2017 report, the tonnage of the CSC was estimated at 5400 tonnes. In 2019, the updated tonnage was 6790 tonnes, a 25.7% increase.

Australia is also pursuing the acquisition of a new fleet of frigates. In June 2018, the Australian government selected BAE Systems to build nine Hunter Class frigates based upon its Type 26 design. Its initial design, as pitched to the government, gave the frigate a weight of 8800 tonnes when fully loaded and a length of 149.9 metres. There are now reports that the ship’s weight is on track to exceed 10,000 tonnes, necessitating a bigger hull. This in turn will affect its speed, acoustic performance and ability to conduct stealthy anti-submarine warfare operations. The Australian Navy’s fleet is now undergoing design changes because the ships have become too heavy, risking a cost blowout for taxpayers and potentially compromising their performance.[17]

With the limited information available to the public, there is reason to be concerned that the weight of the CSC could escalate further. In its filing with the Canadian International Trade Tribunal (CITT), Alion, one of the CSC bidders, alleged that the Type 26 design was not large enough to accommodate the number of sailors Canada had specified and that the ship could not attain the speed required by Canada.

In the case of the berthing capacity, should it be necessary to add more capacity for sailor’s quarters, an increase to the size of the ship may be required. Similarly, if larger engines and more propulsion is required to allow the ship to reach the speed specified in the requirement, then it is likely the size of the ship will need to increase. These issues were never addressed in court proceedings and never addressed by the government, the Navy, Irving or LM. And so, we don’t know what impact either issue would have on the size of the ship. Significantly, a news report on the CITT case stated that the CITT’s dismissal of the complaint was not related to the content of Alion’s complaint, but to a section of the body’s regulations dealing with various trade agreements.[18]

Another issue which could affect ship weight is the SPY-7 radar. At this point, because it is a developmental radar which has yet to be marinized, we cannot know the weight or volume of the radar or how much of its infrastructure and sensors will occupy its superstructure above and below the deck. This could create weight, space and balance issues for the new vessel. We do know for certain that any increase in the length and tonnage of Canada’s CSC, would result in additional performance and cost concerns.

In summary, there is a risk that the CSC tonnage could rise to 8800 tonnes or more. Such an increase would create the same kind of performance and cost concerns experienced by the Australian Navy. An increase in tonnage from 6790 to 8800 represents a 29.6% increase and a corresponding cost increase of $8.6 billion.[19] Attaching a probability of 50% to this weight increase yields an expected cost increase of $4.3 billion.

TECHNICAL RISKS

In December 2019, CBC News reported on a number of concerns industry had raised regarding the systems and weapons that had been selected for the CSC.[20] While not identifying the source of the material, the article reported that industry was claiming that:

“The defence industry briefing presentation points out that the Lockheed Martin-built AN/SPY – 7 radar system – an updated, more sophisticated version of an existing U.S. military system – has not been installed and certified on any warship. A land-based version of the system is being produced and fielded for the Japanese government. The briefing calls it “an unproven radar” system that will be “costly to support” and claims it comes at a total price tag of $1 billion for all of the new ships, which the undated presentation describes as “an unnecessary expenditure.”

The industry briefing also raised concerns about DND’s choice of a main deck gun for the frigates – a 127-millimetre MK 45 described by the briefing as “30-year-old technology that will soon be obsolete and cannot fire precision-guided shells.” The other system it drew attention to was the “inadequate Sea Ceptor Close-In Air Defence system, which is meant to shoot down incoming, ship-killing missiles”.

Owing to the lack of transparency within the Canadian CSC procurement process, it cannot be confirmed whether these assessments are accurate. But they raise a number of critical questions. What is the risk that the chosen systems will not provide the capability necessary to undertake the missions required of the Navy? What is the rationale for the selection of an old gun for a modern warship? What is the cost and risk from both schedule and capability standpoints of choosing systems not yet fielded? Who is going to pay for the development costs of unproven systems?

Interestingly, the US FFG(X) is equipped with the SPY-6 radar and the SeaRAM MK15, Mod31 Close-In Air Defence (CIAD) system. This does not mean that Canada should necessarily have the same suite of systems and weapons. But since we have chosen not to, it certainly is worth finding out why not. These systems were selected by the US Navy because they are proven, in production and represent the lowest risk solution, whilst maximizing commonality across the USN fleet. Replicating these two systems could represent potential for cost savings for Canada. The development, integration, validation and certification for these systems will have been done and paid for by the US Navy. In particular, significant cost savings could materialize with respect to the radar. Through the end of FY2018 the US Navy had spent $545 million (USD) developing the SPY-6 radar and is expected to spend another $472 million (USD) through the end of FY 2025 (for a total of $1,017 million (USD)) on this program.[21] Canada would therefore not have to bear any of these development costs for the SPY-6 radar.

In contrast, the SPY-7 radar is currently a land-based system designed for early warning and ballistic missile defence. There will be costs to convert it for use on warships not dissimilar to the costs borne by the US Navy for SPY-6 development. Canada, with its apparent commitment to put the SPY-7 on its fifteen CSC, Spain with its commitment to put it on its five new F-110 frigates[22] and possibly Japan (as of this date, no final decision taken)[23] would likely bear some of these costs to address items such as antenna mast integration, below-decks configuration and environmental qualification. In addition, Canada would have to bear the costs for verification testing and missile fly-out certification, which involves lease costs for appropriate test facilities (like the US Pacific Missile Range Facility (PMRF)), expenditures of missile inventory and deployment of CSC test ship. As these costs are not clearly specified, the author has factored in a nominal incremental cost to Canada of $100 million to bring attention to these matters.

With respect to the main deck gun, Canada has specified the requirement for a 127 mm gun. It defies logic to think that the LMC/BAE team would propose a deck gun that is apparently no longer in production. However, if the allegation is true, then the reconciliation phase provides the opportunity to make the appropriate substitution. Deck guns that are used or refurbished have no place on what is described as a state of the art warship.

CONCLUSION

Warships are incredibly complex systems. They combine an extremely sophisticated weapons platform for air defence, surface and underwater warfare, with a restaurant, a hotel, an airport, a recreation and fitness centre, an armoury and a sanitation system – all of which must operate in the hostile environment of the open ocean and travel at speeds approaching 30 knots. It is little wonder that the proposals to build the CSC consumed tens of thousands of pages.

As the largest procurement in the history of the Canadian Government, it is vital that the CSC project not be allowed to flounder or run aground. New warships for the Royal Canadian Navy are urgently required to replace the 25-year-old Halifax Class frigates. However, the acquisition process initially adopted by the previous Conservative Government and continued under the current Liberal Government, will very likely produce perhaps the costliest warships (for their size) of any similar ships anywhere in the world.

This runs counter to what Kevin McCoy, President of Irving, indicated in an interview with CBC News in May of 2016. The story quoted McCoy as stating: “What we have said consistently to the Government of Canada is: Canada should pay no more for their warships than other nations with like-minded aspirations.” Paraphrasing McCoy, the story also added that “sticker shock among the public is always a concern, but promised the federal government will pay a fair price for its warships."[24] Canada desperately needs new warships – but they should not be acquired at any cost.

When it was conceived, the intent of the National Shipbuilding Procurement Strategy was indisputably laudable. There was a natural desire to create sustainable well-paying jobs and avoid the boom and bust shipbuilding scenarios that have characterized the industry in the past. The inclination of a federal government that lacked the expertise to conduct a program of this magnitude was to push responsibility and accountability to the private sector. As events are in the process of demonstrating, it was a titanic miscalculation. It was simply the wrong thing to do.

In this particular case, both major political parties – Conservatives and Liberals - have significant culpability for a defective process that has been long, convoluted and expensive. Senior bureaucrats also bear a large responsibility for conceiving of, or acquiescing to, this seriously flawed process. Correcting the flaws in this procurement should be approached not as a partisan exercise, but as a collective public policy challenge where ideas are judged on their quality rather than their party origin.

This paper has provided a snapshot in time concerning what might be expected in terms of costs for the CSC program. However, it would be incomplete if it did not offer some recommendations.

RECOMMENDATIONS

1. Government officials should immediately intervene in the current process to understand the full costs of the program including long term support costs.

2. Government officials should ensure that the suite of selected systems, subsystems and weapons are cost effective and will provide the capability to undertake the missions required of the Navy. Examples of such systems include the radar, CIAD system and main deck gun.

3. Officials must determine whether DND modified the SOR, and if so, why. In the interest of transparency, their findings should be made public.

4. The government should structure a Cabinet sub-committee to oversee the CSC program. Within the bureaucracy, one clear point of accountability should be established and that individual should provide monthly updates on progress made.

5. Close oversight should be maintained by Cabinet and Parliament. The Standing Committee on National Defence should also be provided with regular updates and should conduct regular hearings on this program.

6. The current process should be limited to the acquisition of the first three CSC. A new procurement process should be established for the remaining 12 ships. Every effort should be made to ensure that a full complement of 15 warships is constructed for the Navy.

7. In any new process:

· The government should retain procurement authority;

· The government/Navy should specify its requirements and demand systems and weapons that require minimal integration and that are developed and shipborne-ready. The ship design must be based upon an existing operational ship design.

· The government should allow for the formation of competing industry teams to meet the government’s requirements with each team identifying its accountable team leader, its members, its proposed off-the-shelf design and its proposed shipyard(s). (After all, more than one shipyard is possible). It should not preselect the shipyard or any member of any team as it did in the current process. As with the FFG(X), the government/Navy should be able to specify certain systems as Government Furnished Equipment.

8. As a first step, PSPC and DND officials should consult with industry to obtain their advice and insights on the way ahead.

9. The new process should establish a budget that is realistic and no more than a three-year schedule to enter into a construction contract.

10. The PBO should refer its study to the Auditor General of Canada who should work with the PBO on an urgent basis to undertake a more detailed review of the entire CSC program relating to process and cost.

Full Disclosure Mr. Williams has worked as a consultant for various companies involved in the Canadian Surface Combatant project. These include Alion, Leonardo DRS, Leonardo Defence Systems, and Raytheon. The views presented here are his alone and do not represent the views of the companies he has worked with. All information contained in this article is from publicly available sources.

References

[1] Office of the Parliamentary Budget Officer, The Cost of Canada’s Surface Combatants: 2019 Update, June 21 2019

[2] Murray Brewster, CBC News, June 22. 2019, How much will Canada’s new frigates really cost? The Navy is about to find out.

[3] ISED website, Key Industrial Capabilities

[4] Memorandum to DND’S Program Management Board (PMB), Oct. 27. 2003

[5] Briefing note for ADM(MAT), Annual Performance Review, Q4 FY10/11, May 10, 2011

[6] 8.67 years x $2.2 billion = $19 billion

[7] PSPC Large Vessel Shipbuilding Projects, Arctic and Offshore Patrol Ships: Royal Canadian Navy, July 31, 2020

[8] CBC news, posted July 16, 2010, Canada to spend $9B on F-35 fighter jets.

[9] PBO report, Mar. 10, 2011; An Estimate of the Fiscal Impact of Canada’s Proposed Acquisition of the F-35 Lightning II Joint Strike Fighter.

[10] The Hill Times, May 28, 2012, Government Contentions on F-35 Flawed

[11] Statement by the Department of National Defence on the Parliamentary Budget Officer’s Report on the Canadian Surface Combatant, June 21, 2019.

[12] In the program designation FFG(X), FF means frigate, G means guided-missile ship (indicating a ship equipped with an area-defense anti-air warfare [AAW] system) and (X) indicates that the specific design of the ship has not yet been determined. FFG(X) thus means a guided missile frigate whose specific design has not yet been determined.

[13]All material in this section is extracted from Congressional Research Service Report, Navy Frigate (FFG(X)) Program: Background and Issues for Congress, Updated May 4, 2020

[14] Unit cost (Can $) = Unit cost x 1.35

[15] The War Zone, Is The Navy Missing The Boat By Not Including The Type 26 In Its Frigate Competition? May 29, 2019

[16] Page 16, PBO Report on the cost of Canada’s CSC, 2019 update.

[17] Andrew Tillett, Political Correspondent, Australian Financial Review, June 26, 2022, “Sinking feeling: frigate heads back to drawing board”.

[18] Trade tribunal dismisses Alion's complaint over shipbuilding contracts, Andrea Gunn, Halifax Chronicle Herald, February 1, 2019

[19] According to PBO figures, between 2017 and 2019, the weight increased by 25.7% and the production costs rose by 14.8 million. Weight would account for at least 7.5 million of the cost. An increase in tonnage to 8800 tonnes represents a 29.6% increase and, based upon the same ratio, would equate to an $8.6 billion dollar increase.

[20] Murray Brewster, CBC news, Dec. 23, 2019 “Industry briefing questions Ottawa’s choice of guns, defence systems for new frigates.”

[21] Exhibit P-40, Budget Line Item Justification: PB 2021 Navy; February 2020

[22] Military Aerospace Electronics, Lockheed Martin to provide digital maritime shipboard radar systems for Spanish Navantia F-110 frigates

[23] Reuters: Exclusive: As Japan weighs missile-defence options, Raytheon lobbies for Lockheed’s $300 million radar deal, July 30, 2020

[24] Murray Brewster, CBC News, Canadians won't see price tag for navy frigate replacement until 2019, May 26, 2016.

About The Author

Mr. Williams retired in 2005 after enjoying a 33-year career in the Canadian federal public service. The last ten years of his career were spent in the business of defence procurement, five years as Assistant Deputy Minister Supply Operations Service in Public Works and Government Services Canada followed by five years as Assistant Deputy Minister of Materiel at the Department of National Defence. He is now President of The Williams Group, providing expertise in the areas of policy, strategic planning and procurement. He has authored two books, “Reinventing Canadian Defence Procurement: A View From the Inside” published in 2006 and “Canada, Democracy and the F-35” published in 2012. Mr. Williams is a frequent commentator on issues dealing with military procurement. He can be reached at williamsgroup691@gmail.com.