(Volume 24-09)

By Anne Gafiuk

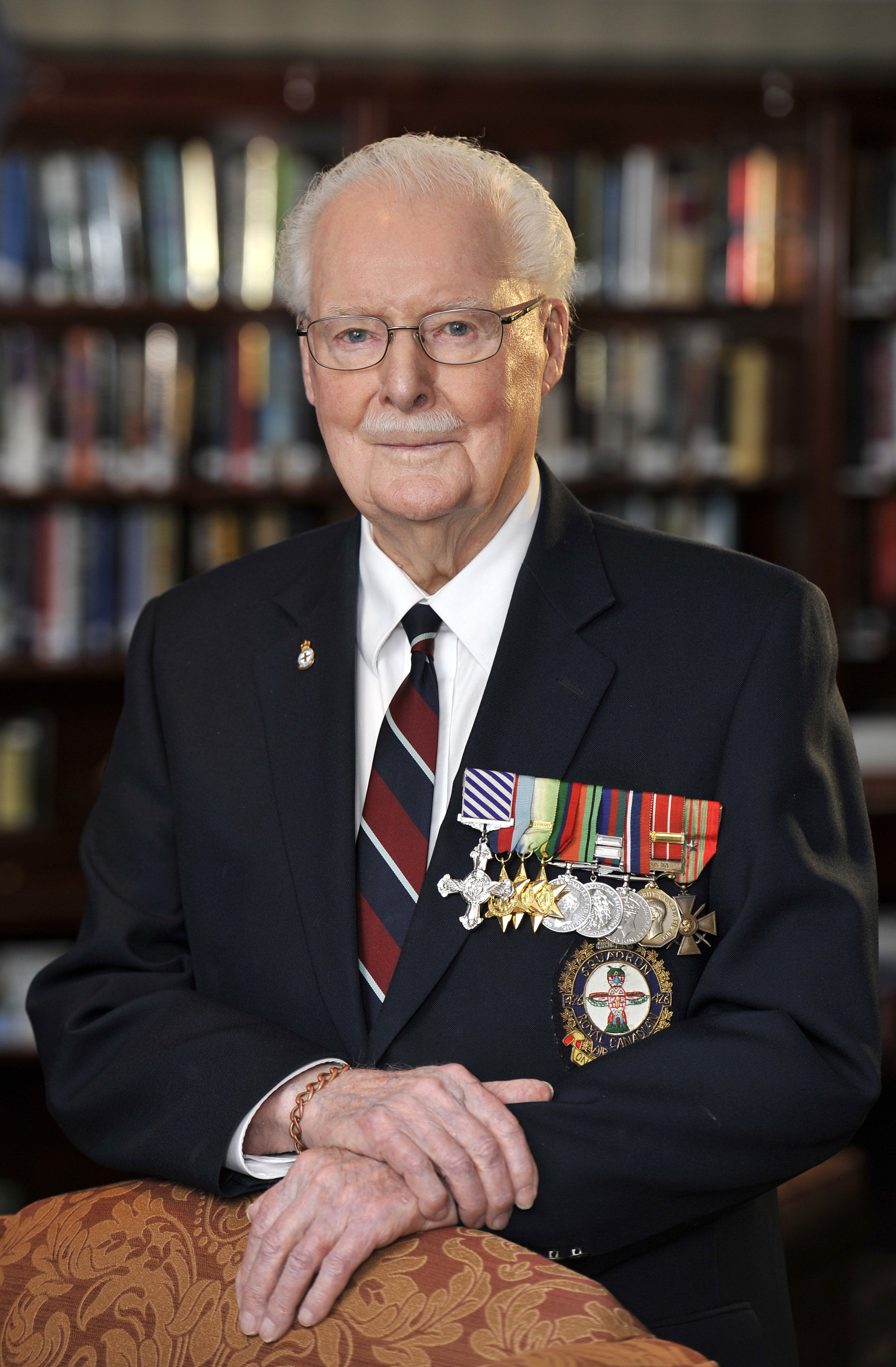

“Have I got another story to tell you,” says Cliff Black, Second World War RCAF veteran.

One of his favourites is a close call with a purloined Flying Fortress while serving overseas as an RCAF Lancaster pilot with No. 419 Squadron. The squadron was part of the Canadian Bomber Command [6 Group] based at Middleton-St George in Yorkshire, England.

This tale, however, took place in Canada in the wilderness of the Lillooet Ranges of the Coastal Mountains of British Columbia. Black was posted at No. 13 Operational Training Unit (OTU), Patricia Bay, now the site of Victoria International Airport. It was late September 1941, on a Sunday. Black was golfing.

Two Anson aircraft had departed from Lethbridge, Alberta, in the late morning of September 21. Their final destination was No. 32 OTU at Pat Bay. The flight Anson N9818 had started its journey from Aircraft Repair Limited in Edmonton, Alberta.

Flying Officer Lloyd “Brookie” Brooks was in charge of one of the planes. “Brookie was sent to pick up one Anson in Edmonton and ferry it back to Pat Bay,” Black recalls. A second airplane was flown by PO “Doc” Sutherland.

Both aircraft had taken off from Kimberley, B.C. after refuelling. They had been flying on top of a broken overcast. In the vicinity of Hope, B.C., however, a front was encountered and both aircraft climbed to 16,000 feet where they entered the clouds. After being in the clouds for two minutes, moderate icing was experienced by Sutherland who decided to turn back, returning to Princeton, B.C. to await more favourable weather conditions.

“Personnel from Pat Bay came to tell us an airplane was missing,” Black says.

They had started searching, but it had been quite cloudy that first day, so crews came back empty. The second day, the weather was better. Soon, Black and another crew member sighted the downed Anson.

“We flew down as low as we could to take a look at it. It was a mess,” he remembers.

Disappointed he was not initially chosen to join the search party, Black approached Wing Commander John Plant, explaining that he had found the plane and wanted to finish the job. Plant put him on the list.

“We flew across in an Electra and landed in Vancouver, then the police drove us up to Hope in a few cars, dropping us off as close as they could so we could start our climb,” he explains.

A base camp had been established near a motel in the area, where they purchased hiking boots and jumpsuits to wear over their uniforms. With 12 others, a mix of RCAF personnel and a few locals, Black set out to climb the mountain.

“We went up a trail and a pretty rough road. There was a shack and from there we started to climb, coming to the top of one mountain,” he says. “It was steep and rocky.”

During the trip, the 24-year-old Black wore thick wool socks, preventing blisters, and brought along a match case he had gotten as a Boy Scout. On the trip, the legs of members of the search party were cramping up.

“We didn’t have food or water ... nothing!” he recalls. “A young fellow from the town and I continued. The rest of them went back. We spent all day climbing, drinking from the streams.”

Finally, Black and the young man, William Richmond, made it to the crash site. There they found the smashed aircraft among huge, rough rocks and bushes. Black and Richmond found two of the three men quickly. Aircraftman Douglas Wortley, 23, and Sergeant Lionel Britland, 21, both from the Lower Mainland, had caught a ride home with “Brookie” Brooks, 37, an American ferrying aircraft for the RCAF. They wanted to surprise their families. Britland and Wortley’s bodies were recovered. But Brooks’s had yet to be found.

“I thought: That bastard! He bailed out and left those kids! He would have been the only one with a parachute. Then I noticed a couple of heels in the bushes. Brooks, a big man, had gone right through the windshield of the aircraft. We pulled him out and getting him down, we lay the other two men beside him.”

As the sun was setting, light aircraft dropped supplies to Black and Richmond, including a hatchet, revolver, canvas, rope, sleeping bags and food. The supplies were attached to pieces of red cloth acting as parachutes, slowing the boxes as they descended.

Using the hatchet to chop some wood, the two men made a fire. They spent two days and nights on the mountain. Two bears nearby worried the men.

“If the fire got low, they might get closer to us,” recalls Black.

Black fired shots with the revolver at the rocks close to the bears, the shots ricocheting off the rock. That was enough. They never came down. By the third day, Flight Sergeant “Carney” Carnahan arrived with two packhorses and other members of a second rescue party. Because of the grisly scene that greeted them, Black was asked to cover the faces of the deceased. They used the red cloth from the supply drops to wrap the men’s faces.

Discussion ensued as to what to do with the bodies of Brooks, Britland and Wortley. Brooks was laid on one of the horses, but the horse’s legs buckled.

As the only officer present, Black was in charge. Since the horses could not carry the dead men, and they couldn’t bury them, he decided cremation was the best option.

“We broke up boxes from the drop, plus found scruff from the few dead trees, building what would be a pretty good fire, with a bit of fuel from the tanks of the Anson,” he says.

They took the airmen’s belongings out of their pockets, leaving their clothes on. A boulder placed on Brooks’s cap marked the accident’s location. Black couldn’t bear the thought of watching these men burn, so he packed the hatchet and revolver, and asked Carney to lead the way back down the mountain. The match was struck. The fire was lit. Black and Carnahan departed, leaving Richmond to return with the second search party.

But slowly Black and Carnahan realized they had a problem. “Trees and rocks started to look the same; within another two or three hours, we didn’t know where we were,” he says. “It never occurred to me how could you get lost on the huge mountain, but once you get down in the big trees ...”

Black and Carnahan were lost, the sun setting upon Old Settler Mountain once again. Another fire would be in order. Black stared into the distance, seeing the story playing out once more in his mind. This time, however, a bear did join them.

“‘My God, Carney! There’s a bear!’” yelled Black to his friend, while screaming at the bear to back off. “’Make lots of noise!’ I shouted to Carney.”

Remembering his companion’s perplexed look, Black laughs. Together they kept yelling at the bear to back off, though it didn’t seem too interested in coming after them. “I could see the staining around her [the bear’s] mouth from eating berries.”

Black told Carnahan to prepare himself to receive the hatchet if ever she chose to attack him.

“I’ll play dead and when she has me, you try to cut her backbone!”

Carnahan threw a piece of wood at the bush beside the bear. She immediately took off. “We watched for a minute or two and she kept going. She must have thought something was tracking her!”

Exhausted, hungry and thirsty, they took off their boots, and tried to warm them by the fire.

“It was a beautiful night.”

The next morning, they continued their climb down the mountain, following the sun in the east. Around 1000 hours, the smell of fresh bread filled the air. A little house appeared nearby. Holding a knife, a man came out of the house, recognizing the two men as the lost boys. The news of their disappearance had spread.

With fresh bread to eat, Black and Carnahan asked for the location of the nearest road, which was through some nearby bushes. A car stopped minutes later, driving them back to their motel, where the other guys were getting ready to leave.

An old trapper told Black he knew a grizzly was trailing them, and worried for their safety, to which Black told him all about their encounter with the bear. Black was now ready to go home.

“I just wanted to get the hell out of there,” he says.

He and Carnahan were put on the train back to Vancouver, ferried to the island. By October 3, he was flying again.

“I still dream about this bear in the middle of the night,” Black says. His wife, Sue, confirmed this to be true.