By Brian Forbes, Chair of the National Council of Veteran Associations and Chair of The War Amps Executive Committee

The National Council of Veteran Associations (NCVA) continues to take the position that there is much to do in improving veterans’ legislation so as to address the financial and wellness requirements of Canada’s veterans’ community. This is particularly so with respect to the Pension for Life (PFL) provisions originally announced in December 2017 and formally implemented on April 1, 2019.

It has become self-evident that the greater majority of disabled veterans are not materially impacted by the PFL legislation in that the new benefits under these legislative and regulatory amendments have limited applicability – indeed, some seriously disabled veterans are actually worse off.

In our considered opinion, this PFL policy fails to satisfy the Prime Minister’s initial commitment in 2015, in response to the Equitas lawsuit, to address the inadequacies and deficiencies in the New Veterans Charter/Veterans Well-being Act (NVC/VWA) and continues to ignore the “elephant in the room” that has overshadowed this entire discussion.

As stated in our many submissions to VAC and Parliament, the Government has not met veterans’ expectations with regard to the fundamental mandated commitment to “re-establish lifelong pensions” under the Charter so as to ensure that a comparable level of financial security is provided to all disabled veterans and their families over their life course, regardless of where or when they were injured. This financial disparity between the Pension Act and NVC/VWA compensation was fully validated by the Parliamentary Budget Office’s report issued on February 21, 2019, which clearly underlined this blatant discrimination.

With specific reference to the provisions of the legislation that became effective April 1, 2019, the statutory and regulatory amendments reflect the Government’s inadequate attempt to create a form of “pension for life” (PFL) which includes the following three elements:

1. A disabled veteran has the option to receive the original lump sum disability award in the form of a Pain and Suffering Compensation (PSC) benefit representing a payment in the maximum amount of $1,297 (as of January 1, 2023) for life. For those veterans in receipt of PSC, retroactive assessment would potentially apply to produce a reduced monthly payment for life for such veterans. In effect, Veterans Affairs Canada (VAC) has simply converted the amount of the lump sum disability award into a form of a lifetime annuity as an option for those disabled veterans who are eligible.

2. An Additional Pain and Suffering (APSC) benefit has essentially replaced the Career Impact Allowance (Permanent Impairment Allowance) under the NVC/VWA, with similar grade levels and monthly payments that reflect a non-taxable non-economic benefit but is substantially limited in its application to those veterans suffering a “permanent and severe impairment which is creating a barrier to re-establishment in life after service.”

3. A consolidated Income Replacement Benefit (IRB), which is taxable, combined four pre-existing benefits with a proviso that the IRB will be increased by one per cent every year until the veteran reaches what would have been 20 years of service or age 60. It is not without financial significance that the former Career Impact Allowance and Career Impact Allowance Supplement have been eliminated from the IRB package to the detriment of certain veterans as identified by the aforementioned Parliamentary Budget Office report in February 2019.

It is readily apparent that significant amendments to the NVC/VWA are required so as to address the proverbial “elephant in the room” in that the PFL legislation fails to satisfy the priority concerns of the veterans’ community in relation to:

(i) Resolving the significant disparity between the financial compensation paid to disabled veterans under the Pension Act and the NVC/VWA; and

(ii) Ensuring that no veteran under the NVC/VWA receives less compensation than the veteran under the Pension Act with the same disability or incapacity in accordance with the "one veteran - one standard" principle.

It is totally unacceptable that we continue to have veterans’ legislation in Canada that provides a significantly higher level of compensation to a veteran who is injured prior to 2006 (date of enactment of the New Veterans Charter) when compared to a veteran who is injured post‑2006. If applied to the Afghanistan conflict, this discrimination results in veterans of the same war having totally different pension benefits.

During the course of discussions following Budget 2017 leading up to the Minister’s announcement, there was considerable concern in the veterans’ community, which proved to be well founded, that the Government would simply establish an option wherein the lump sum payment (PSC) would be apportioned or reworked over the life of the veteran for the purposes of creating a lifelong pension. NCVA and other veteran stakeholders, together with the Ministerial Policy Advisory Group (MPAG), strongly criticized this proposition as being totally inadequate and not providing the lifetime financial security that was envisaged by the veterans’ community and promised by the Prime Minister in his 2015 election campaign.

It is fair to say that the reasonable expectation of veteran stakeholders was that some form of substantive benefit stream needed to be established that would address the financial disparity between the benefits received under the Pension Act and the NVC/VWA for all disabled veterans.

It has been NCVA’s consistent recommendation to the Minister and to the department that VAC should adopt the major conclusions of the MPAG Report formally presented to the Veterans Summit in Ottawa in October 2016 (and directly to the Minister in January 2020) together with the recommendations contained in the NCVA Legislative Program. (For the full text of the NCVA recommendations, see https://ncva-cnaac.ca/en/legislative-program/).

Both of these reports proposed the combining of the best provisions of the Pension Act and the best provisions of the NVC/VWA resulting in a comprehensive pension compensation and wellness model that would:

a) treat all veterans with parallel disabilities in the same manner; and

b) eliminate the artificial cut-off dates that arbitrarily distinguish veterans based on whether they were injured before or after 2006.

In this context, we strongly encourage the Government to seriously consider the implementation of the following major recommendation of the MPAG as a first step to addressing this problem of the “elephant in the room” and establishing the initial components of our proposed comprehensive pension compensation wellness model:

“[T]he enhancement of the Earnings Loss Benefit/Career Impact Allowance as a single stream of income for life, the addition of Exceptional Incapacity Allowance, Attendance Allowance and a new monthly family benefit for life in accordance with the Pension Act will ensure all veterans receive the care and support they deserve when they need it and through their lifetime.”

In specific terms, we would also suggest that the following steps would dramatically enhance the legislative provisions relevant to the present PFL concept and go a long way to satisfying the “one veteran – one standard” approach advocated by NCVA and the veterans’ community and ostensibly followed by VAC as a basic principle of administration:

1. Liberalize the eligibility criteria in the legislation and regulatory amendments for the new APSC benefit so that more disabled veterans actually qualify for this benefit – currently, only veterans suffering from “a severe and permanent impairment creating a barrier to re-establishment in life after service” will be eligible. It bears repeating that the greater majority of disabled veterans simply will not qualify for this new component of the proposed lifelong pension.

In NCVA’s 2018 Legislative Program, we argued that the veteran’s disability award (PSC) initially granted should be a major determinant in evaluating APSC qualifications. The ostensible new criteria employed by VAC as set out in the regulatory amendments for APSC qualification represent, in our judgment, a far more restrictive approach when compared to the PSC evaluation.

In effect, it is the position of NCVA that this employment of the Disability Award (PSC) percentage would produce a more straightforward and easier‑understood solution to this ongoing issue of APSC eligibility.

The adoption of this type of approach would have the added advantage of augmenting the PFL so as to incorporate more disabled veterans and address the fundamental parity question in relation to Pension Act benefits.

2. Create a new family benefit to parallel the Pension Act provision in relation to spousal and child allowances to recognize the impact of the veteran’s disability on his or her family.

3. Incorporate the special allowances under the Pension Act, i.e., Exceptional Incapacity Allowance and Attendance Allowance, into the NVC/VWA to help address the financial disparity between the two statutory regimes.

In over 40 years of working with The War Amps of Canada, we have literally handled hundreds of special allowance claims and were specifically involved in the formulation of the Exceptional Incapacity Allowance and Attendance Allowance guidelines and grade profiles from the outset. We would indicate that these two special allowances, EIA and AA, represent an integral portion of the compensation available to war amputees and other seriously disabled veterans governed by the Pension Act.

It is of further interest in our judgment that the grade levels for these allowances tend to increase over the life of the veterans as the “ravages of age” are confronted – indeed, non‑pensioned conditions such as the onset of a heart, cancer or diabetic condition, for example, are part and parcel of the EIA/AA adjudication uniquely carried out under the Pension Act policies in this context.

As a sidebar, it is interesting that VAC refers to its Caregiver Recognition Benefit of $1,000 a month as an indication of the Government’s attempt to address the needs of families of disabled veterans. What continues to mystify the veterans’ community is why the Government has chosen to “reinvent the wheel” in this area when addressing this need for attendance/caregiving under the NVC/VWA.

For many decades, Attendance Allowance (with its five grade levels) has been an effective vehicle in this regard, providing a substantially higher level of compensation and more generous eligibility criteria to satisfy this requirement.

In this context, it is noteworthy that the spouses or families of seriously disabled veterans often have to give up significant employment opportunities to fulfill the caregiving needs of the disabled veteran – $1,000 a month is simply not sufficient recognition of this income loss. VAC should return to the AA provision and pay such benefit to the caregiver directly if so desired.

We would strongly suggest that VAC pursue the incorporation of the EIA/AA special allowances into the NVC/VWA with appropriate legislative/regulatory amendments so as to address these deficiencies in the PFL

4. Establish a newly‑structured Career Impact Allowance that would reflect the following standard of compensation: “What would the veteran have earned in his or her military career had the veteran not been injured?” This form of progressive income model, consistently used by the Canadian courts in addressing “future loss of income” for injured plaintiffs, has been recommended by the MPAG and the Veterans Ombudsman’s Office. This concept would be unique to the NVC/VWA and would bolster the potential lifetime compensation of a disabled veteran as to his or her projected lost career earnings as opposed to the nominal one per cent increase provided in the proposed legislation.

In summary, it is fundamental to understand that it was truly the expectation of the disabled veteran community that the “re‑establishment” of a PFL option would not just attempt to address the concerns of the small minority of disabled veterans but would include a recognition of all disabled veterans who require financial security in coping with their levels of incapacity.

As a final observation, VAC consistently talks of the significance that the Government attaches to the wellness, rehabilitation and education programs under the NVC/VWA. As we have stated on a number of occasions, we commend VAC for its efforts to improve these important policies. NCVA recognizes the value and importance of wellness and rehabilitation programs; however, we take the position that financial security remains a fundamental necessity to the successful implementation of any wellness or rehabilitation strategy. It is readily apparent that this is not a choice between wellness and financial compensation as advanced by the Minister and the Prime Minister, but a combined requirement to any optimal re‑establishment strategy for medically released veterans.

Ideally, we would like to believe that VAC, working together with relevant Ministerial Advisory Groups and other veteran stakeholders, could “think outside the box” and create a comprehensive program model that would essentially treat all veterans with parallel disabilities in the same manner as to the application of benefits and wellness policies.

In our judgment, the adoption of this innovative policy objective would have the added advantage of signaling to the veterans’ community that VAC is prepared to take progressive steps to tackle legislative reform beyond the current PFL provision so as to address this fundamental core issue of concern to Canada’s veterans and their families.

Let us now actually compare the present pension benefit regimes and then take a look at what VAC legislation would provide to veterans and their families if the aforementioned NCVA proposals were adopted by the Government.

For 100 percent pensioners (at maximum rate of compensation):

PENSION ACT (2023)

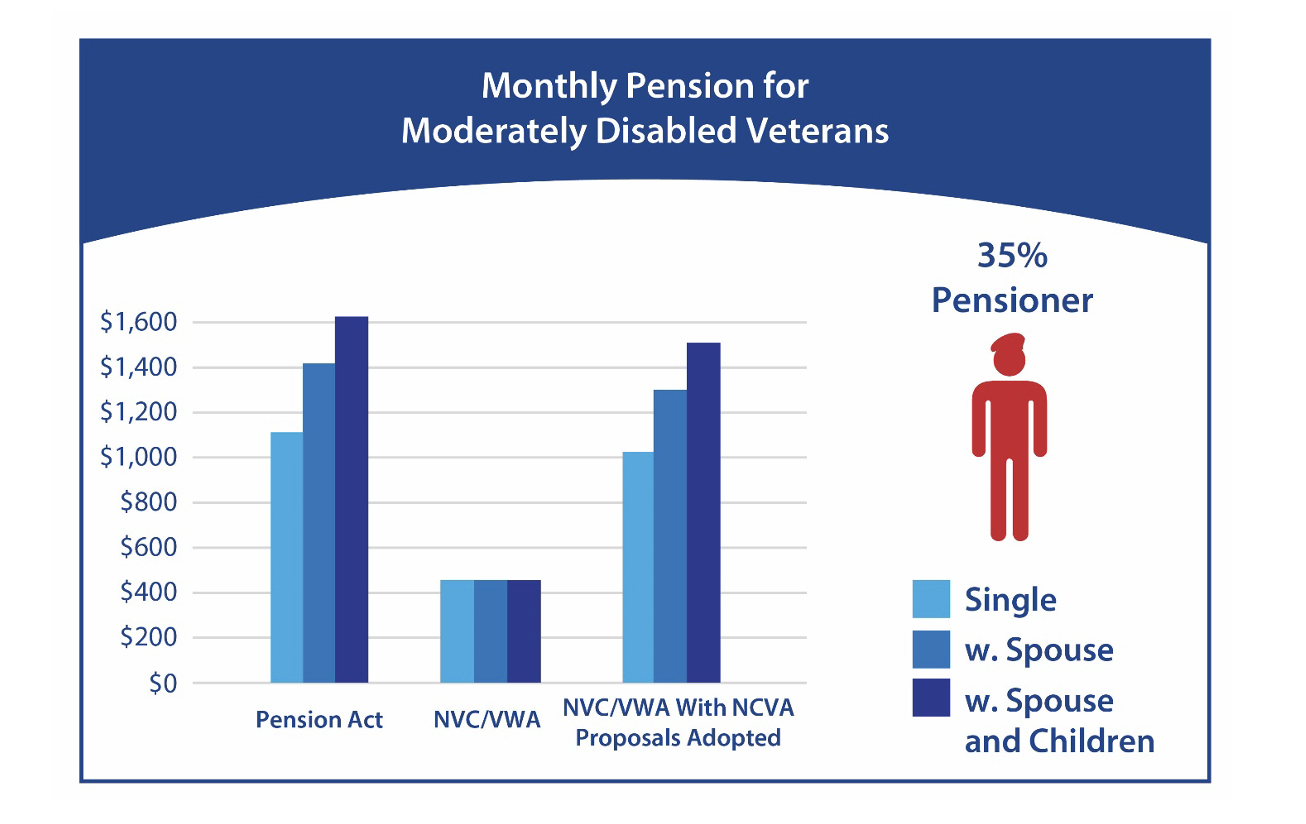

It is of even greater significance to recognize the impact of the Pension for Life policy which became effective on April 1, 2019, on those disabled veterans who might be considered moderately disabled as the disparity in financial compensation between the statutory regimes is even more dramatic.

Let us take the illustration of a veteran with a 35 percent disability assessment:

• Assume the veteran has a mental or physical injury which is deemed not to be a “severe and permanent impairment” – the expected eligibility reality for the greater majority of disabled veterans under the NVC/VWA.

• The veteran enters the income replacement/rehabilitation program with SISIP LTD as the first responder or the IRB/rehabilitation program with VAC.

• Ultimately the veteran finds employment in the public or private sector attaining an income of at least 66‑2/3 percent of his or her former military wage.

It is important to be cognizant of the fact that, once such a veteran earns 66‑2/3 percent of his or her pre‑release military income, the veteran is no longer eligible for the SISIP LTD or the VAC IRB and, due to the fact that the veteran’s disability does not equate to a “severe and permanent impairment,” the veteran does not qualify for the new Additional Pain and Suffering Compensation benefit.

Therefore, the comparability evaluation for 35 percent pensioners would be as follows under the alternative pension schemes:

We would underline that this analysis demonstrates the extremely significant financial disparity which results for this type of moderately disabled veteran. It is also essential to recognize that over 80 percent of disabled veterans under the NVC/VWA will fall into this category of compensation. Unfortunately, the perpetuation of the inequitable treatment of these two distinct classes of veteran pensioner is self-evident and remains unacceptable to the overall veterans’ community.

Finally, let us consider the impact on this analysis in the event the NCVA proposals were to be implemented as part and parcel of an improved NVC/VWA:

In summary, this combination of augmented benefits proposed by NCVA would go a long way to removing the discrimination that currently exists between the PA and the NVC/VWA and would represent a substantial advancement in the reform of veterans’ legislation, concluding in a “one veteran – one standard” approach for Canada’s disabled veteran population.

In addition, should VAC implement NCVA’s recommendations (as supported by the OVO and MPAG) with respect to a newly structured CIA, the IRB would be substantially enhanced by incorporating this progressive future loss of income standard as to “What would the veteran have earned in his or her military career had the veteran not been injured?”

It is noteworthy that the current IRB essentially provides 90 percent of the former military wage of the veteran, together with a limited one percent increment dependent on the veteran’s years of service, resulting in an inadequate recognition of the real loss of income experienced by the disabled veteran as a consequence of his or her shortened military career.

The new conceptual philosophy of this future loss of income approach parallels the longstanding jurisprudence found in the Canadian courts in this context and is far more reflective of the actual financial diminishment suffered by the disabled veteran (and his or her family). This would represent a major step forward for VAC in establishing a more equitable compensation/pension/wellness model.

As a final observation, it is noteworthy that the Prime Minister, various Ministers of the Department and senior governmental officials of VAC, in their public pronouncements from time to time, have emphasized that additional benefits and services are uniquely available under the NVC/VWA with respect to income replacement, rehabilitation, and wellness programs.

NCVA fully recognizes the value and importance of these programs and we commend VAC for its efforts to improve the Department’s wellness and educational policies. However, it should be noted that a number of programs dealing with essentially parallel income replacement and rehabilitation policies already exist under the PA regime by means of services and benefits administered by the Department of National Defence (DND) through their SISIP LTD insurance policy and Vocational Rehabilitation (VOC REHAB) Programs.

It is not without significance in this evaluation that, at the time of the enactment of the New Veterans Charter in 2006, VAC committed to eliminating SISIP LTD and VOC‑REHAB programs and creating a new universal gold standard in regard to income replacement and wellness policies which would be applicable to all disabled veterans in Canada. The reality is that the SISIP LTD and VOC‑REHAB insurance policy has been and continues today to be “the first responder” for the greater majority of disabled veterans who have been medically released from the Canadian Armed Forces in relation to both the PA and the NVC/VWA.

As a fundamental conclusion to our position, we would like to think that the Government could be convinced that, rather than choosing one statutory regime over the other, a combination of the best parts of the PA and the best parts of the NVC/VWA would provide a better compensation/wellness model for all disabled veterans in Canada.