Volume 26 Issue 5

By Todd Robson

When looking back at the great wars of the 20th century, we have access to textbooks, newsreels, the writings of historians, and even grainy, black and white films that try to capture these events in a factual manner. Quite often those stories give us a look at the historic proportions of certain events and their outcomes, but the personal stories of the soldiers who answered the call to serve their country, who fought in the battles, and ensured our freedom, are seldom told.

History is best understood through the stories and mementos of those who lived it. A medal heroically earned and awarded, a piece of the uniform worn each long day during the war, or a personal handwritten letter sent home from an ocean away – it’s those items that capture the deeply personal side of war and the life of a soldier. Historic artifacts and personal items create a compelling story and preserve the memories for family members, for future generations, and for museum curators who are diligent in their efforts to illuminate the past and to keep the ongoing narrative of the world’s history.

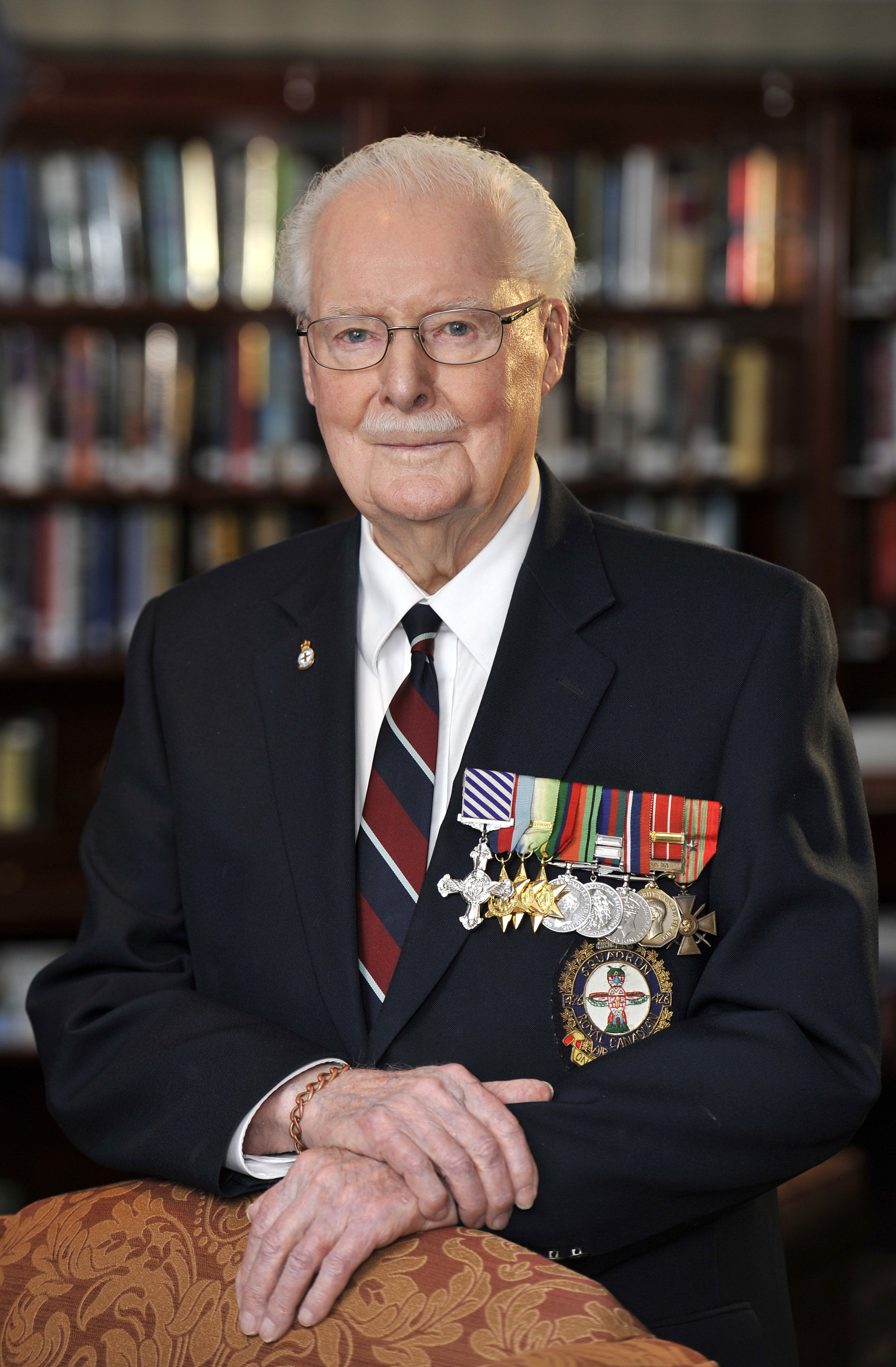

Honorary Colonel Kevin McCormick of the Irish Regiment of Canada, serves as President and Vice-Chancellor of Huntington University, in Greater Sudbury, Ontario. Over the span of two decades, HCol McCormick has funded and conceived initiatives such as the Crown and Canada and Project Honour and Preserve, in an effort to find and repatriate military items and artifacts. He ensures that they find their way back into the hands of their rightful owners, or are given to museums and organizations that will share the story of each item, so that the personal sacrifices of soldiers will be not be forgotten.

“The donation of items such as these, in many instances over 100 years old, is not merely about the physical item but the personal story contained within it,” said McCormick. “To hold one of these historic medals or handwritten notes in your hand and realize it represents a greater story – the life of a young man going off to fight in World War I, leaving a wife and children behind in service of both his country and the world – is truly inspiring.”

Through Crown and Canada in particular, McCormick promotes British history and British military history while raising awareness of the honoured role of the Sovereign, Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II and her family in our nation’s history, and especially the role it holds within the Canadian Armed Forces. On his own time, and self-funded, HCol McCormick has travelled more than 100,000 kilometres finding, acquiring and then returning artifacts and items pertaining to British and Canadian history and heritage to museums, families, or governments.

“I’m very proud to play a small role in ensuring that the rich history of the British military is both preserved and honoured for future generations,” said McCormick. “Canada and Britain have a long history of military service and collaboration. I have travelled across Canada in an effort to ensure that the contributions of the British military, in concert with the women and men of the Canadian Armed Forces, are celebrated with great respect.”

If families can’t be found, HCol McCormick repatriates the items to museums and governments. They find rightful homes in Canadian institutions and national landmarks such as the Royal Military College of Canada, the National War Memorial, various national battlefields, the National Peace Tower, Tomb of the Unknown Soldier and many others. With special attention and focus, McCormick has also made presentations and donations to numerous British museums and military units. This past February, HCol McCormick was recognized for his work through the Crown and Canada initiative in the House of Commons. He was joined in Ottawa, for the official reading and a presentation, by the Honourable Harjit Singh Sajjan, Minister of National Defence of Canada. Also on hand that day was the most Senior Military Adviser for Britain, Brigadier Nicholas Orr.

“It is becoming of increasing importance that we recall not just the sacrifice of these soldiers but the sheer horror of the wars and the tolls they took on families, our country and nations around the globe,” said Brigadier Orr, United Kingdom Defence and Military Adviser and Head of British Defence Liaison Staff, for the British High Commission.

According to Brigadier Orr, who has also served previously in Canada at CFB Gagetown, in the Tactics School (1995-1997), and in CFB Suffield, (2001-2003), HCol McCormick’s efforts are recognized and appreciated both at home and internationally.

“In Canada, America and Britain, we know museums can’t exist by themselves. Kevin’s efforts are ensuring they are able to change, refresh their offering - continue to be living. Kevin’s work keeps museums around the world alive, with new sides of history. We need constant reminders of our history or else we forget at our peril. These objects are living reminders and show people the horror of war and that we must never return to that time or place again,” Orr reiterated.

HCol McCormick has been acknowledged and thanked for his efforts on Parliament Hill and even Buckingham Palace. In 2018, HCol McCormick was personally invited and attended the 70th Birthday Patronage Celebration of His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales at Buckingham Palace. On that occasion he made a donation to the future King consisting of historic military scrolls and other artifacts, dating back to 1872, bearing the signatures of members of the London Irish. The items were accepted by retired Major General Sir Sebastian J. Roberts and given to the regimental museum.

For HCol McCormick, at heart, the mission is to preserve history for generations to come, while raising awareness about the inextricable link between Canada’s military history, Britain and the Royal Family.

“Members of the Royal Family continue to hold roles within many of Canada’s military units and in doing so are powerful symbols of the relationship between Britain and Canada,” says HCol McCormick. “Our two nations fought side by side, through two world wars, which is why I endeavour to honour and preserve the military history of both Canada and Britain. I am compelled by history to educate and make sure no one takes for granted the peace, security and amazing sacrifices so many young men and women made so that we could enjoy the lives we live in freedom

today.”