(Volume 24-01)

By David Pugliese

As modern combat forces rely increasingly on space-based technology, the Canadian Armed Forces is committing more resources to satellites. BGen Blaise Frawley discusses some of these programs.

In the last decade, space has begun to play a greater role for the Canadian Armed Forces. Space-based systems have already had a significant place in the lives of the Canadian public, which relies on such assets for everything from banking transactions to daily reports about the weather.

In the military realm, Canadian soldiers now regularly use space-based assets to operate effectively on the battlefield. Such systems do everything from allowing long-range communications to guiding weapons to their targets. The Department of National Defence employs space systems to monitor the maritime approaches of the nation and conduct surveillance on locations around the world.

And with potentially billions of dollars of new projects planned for the future, space operations are on the way to becoming even more central to the effectiveness of the Canadian military. “For us in the Canadian Armed Forces, space is critical,” Brigadier-General Blaise Frawley, Director General of Space, explained in an interview with Esprit de Corps. “The effects that we provide now (because of space assets) support all of the joint players within the Canadian Armed Forces, both domestically and deployed overseas.

Frawley, whose appointment was announced on June 9, 2016, noted that the Royal Canadian Air Force has now taken responsibility for the military’s space programs. It is a natural fit, he added.

The service had a lot of experience with space, starting in the 1960s. “The way we look at this is that space is now delivered by the RCAF but for the joint warrior — so the Army, Navy, Air Force and SOF (special operations forces) warriors,” he said.

Collaboration with allies, industry and other government departments is key to moving forward, Frawley added.

He wants to stay the course for now and deliver the same professional capabilities that have been offered over the years.

But Frawley said he also wants the RCAF to start understanding how it can “grow” the space capability. “We do have a mandate to do that,” Frawley explained. “We’re looking at that and creating a vision for the RCAF commander so we can really understand where we are going to be 10 or 20 years from now.”

After that vision is developed, the RCAF can set about planning how to achieve that end-goal.

Frawley outlined for Esprit de Corps a number of key space programs. They include:

MERCURY GLOBAL

Canada announced in late 2011 that it was joining the U.S. Wideband Global Satellite (WGS) program, contributing $337-million for construction of a ninth satellite as well as operational support costs. Canada is investing as part of a consortium that includes four other countries — Denmark, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and New Zealand — all of which will gain access to the system in proportion to their individual contributions. In exchange for its financial contribution, the Canadian Armed Forces will have access to the Wideband Global Satellite system until 2031.

“Wideband is quite critical to support our joint warriors, both domestically and deployed,” Frawley said.

The Canadian military has already been using the WGS network through interim satellite ground terminals or through allied systems. That use began in May 2012.

In addition, the CAF is spending another $59-million to construct three anchor stations in Canada for the WGS system. In 2014, General Dynamics Canada Ltd. of Ottawa was awarded the contract to build those anchor stations, which will allow communication with the Wideband Global Satellite constellation and link that to the existing CAF communications infrastructure.

The Canadian military will also buy portable satellite communications terminals to allow its commanders on overseas missions to make use of the U.S. Air Force’s WGS network. It wants to buy three types of strategic deployable terminals.

One type would be capable of being operated by an individual and would be small enough to be able to be transported as carry-on luggage on an aircraft. A second type would be the size of check-in luggage, and have an increased ability to transmit information to the digital battlefield.

The third type, called the Heavy Strategic Deployable Terminal, would be able to provide a deployable very high data throughput capability and would be operated by a small team at headquarters level.

The terminals will allow the Canadian Armed Forces to deliver voice, image and data between deployed headquarters and commanders back in Canada.

Bids were submitted December 8. The Canadian military has set aside up to $20-million for the project to acquire the deployable terminals.

The strategic deployable terminals to be purchased would provide seamless interoperability via the Wideband Global Satellites system to the anchor stations as well as allied WGS-certified stations.

But why take part in WGS? The Canadian military was spending approximately $25-million per year on satellite communications capacity acquired from commercial operators. The cost to maintain that status quo was expected to increase significantly during the next 20 years, according to military officers.

The Canadian government has said it decided to take part in WGS because its military needed assured access to satellite communications instead of relying on commercial capacity. In addition, participation in WGS is cheaper than using commercial services, government officials added.

MEOSAR

In 2015, Canada decided to proceed with a project to provide search and rescue (SAR) repeaters for the U.S. Air Force’s next generation of global positioning system (GPS) satellites.

The repeaters provided by Canada’s Medium Earth Orbit Search and Rescue (MEOSAR) satellite project will significantly cut down on the time it takes to locate a distress signal, Canadian military officers say.

The plan would see the installation of the search-and-rescue repeaters on the USAF’s GPS 3 satellites.

Frawley calls MEOSAR “a great capability.” “We are in implementation right now,” he said. “We’re in the process of fitting one of our SAR receivers within one of the satellites.”

The MEOSAR satellite project, which will also include the construction of three ground stations, is expected to cost Canada between $100-million and $249-million, according to the defence acquisition strategy document.

Once in orbit 22,000 kilometres above the Earth, a MEOSAR repeater will be able to detect signals from emergency beacons and retransmit the signals to receiver stations on the ground. The emergency messages can then be sent to appropriate authorities so that people in danger can be quickly located and rescued.

MEOSAR will provide a more capable system to COSPAS–SARSAT (Cosmicheskaya Sistyema Poiska Avariynich Sudov – Search and Rescue Satellite Aided Tracking), according to Canadian military officers.

COSPAS–SARSAT is an international satellite-based search and rescue distress alert detection system established by Canada, France, the former Soviet Union, and the U.S. in 1979. It is credited with saving more than 33,000 lives since its inception.

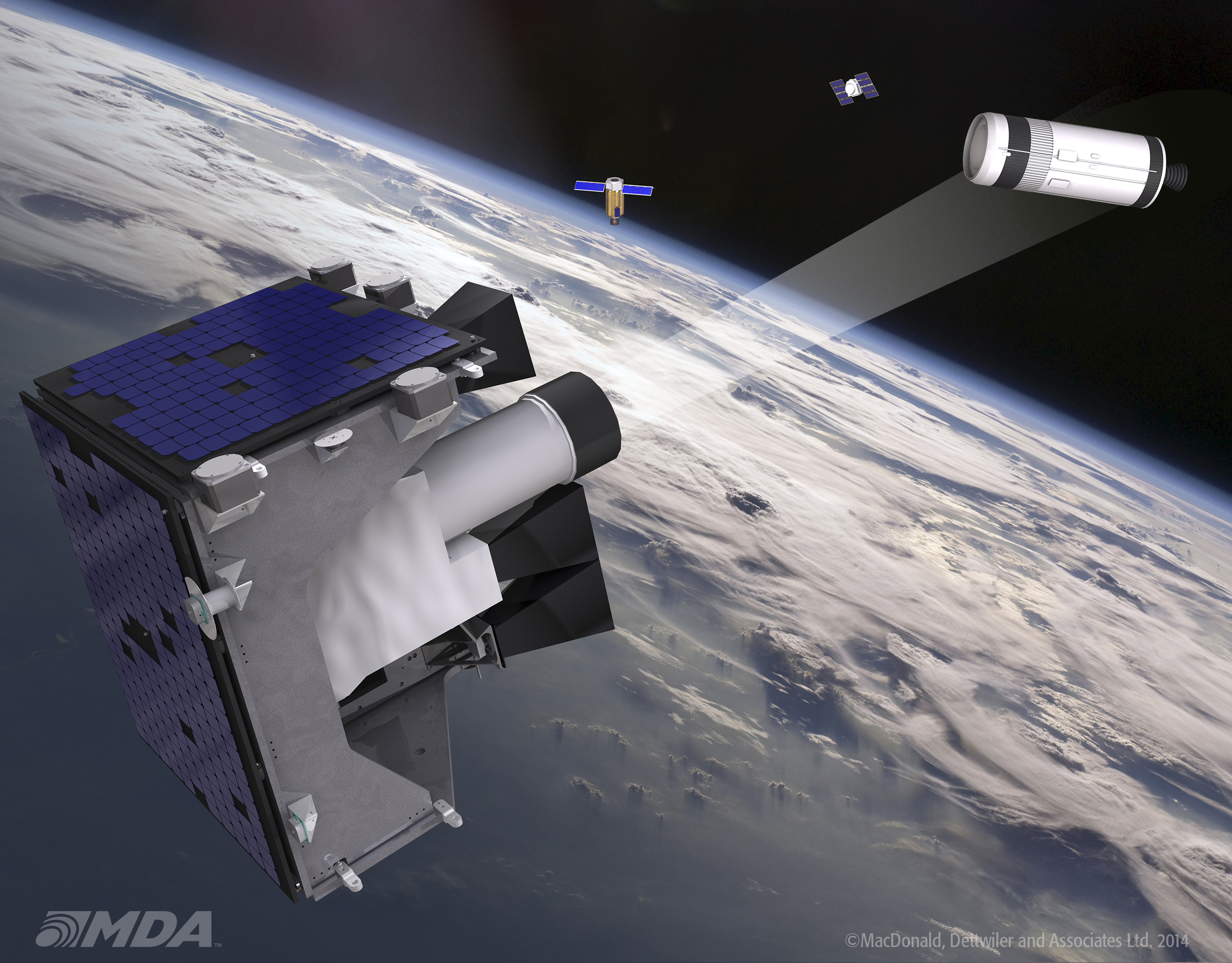

Surveillance of Space: SAPPHIRE

With the 2013 launch of the Sapphire satellite, the Canadian military received, for the first time, its own spacecraft.

Sapphire is Canada’s first-ever dedicated military operational satellite.

The Sapphire satellite, with its electro-optical sensor, tracks space objects in high Earth orbit as part of Canada’s contribution to space situational awareness. Data from Sapphire also contributes to the U.S. Space Surveillance Network, Frawley noted.

Responsible for protecting North America from aerospace threats, NORAD, which is based in Colorado Springs, Colorado, receives its information from that network.

The sensor also provides information to the Department of National Defence and the Canadian Armed Forces about the location of foreign satellites as well as on the whereabouts of orbiting debris, which could pose a hazard to satellites and other spacecraft. In addition, it also allows Canada to gather data about objects, such as space junk, re-entering the Earth’s atmosphere.

Canada’s military has contributed to the surveillance of space mission previously using ground-based telescopes.

But space-based sensors such as Sapphire have a major advantage as ground-based systems can only be used at night. In addition, their performance can be limited by weather or excessive clouds.

Sapphire has a five-year mission life, according to the satellite’s prime contractor MDA Corp., of Richmond, British Columbia.

MDA was award the $66-million contract to build Sapphire in October 2007. The Sapphire contractor team also included Terma A/S of Herlev, Denmark; COM DEV International of Cambridge, Ont.; and Surrey Satellite Technology Ltd. of Surrey, England.

MDA also operates the satellite from its Richmond facilities for the Department of National Defence.

SURVEILLANCE OF SPACE 2

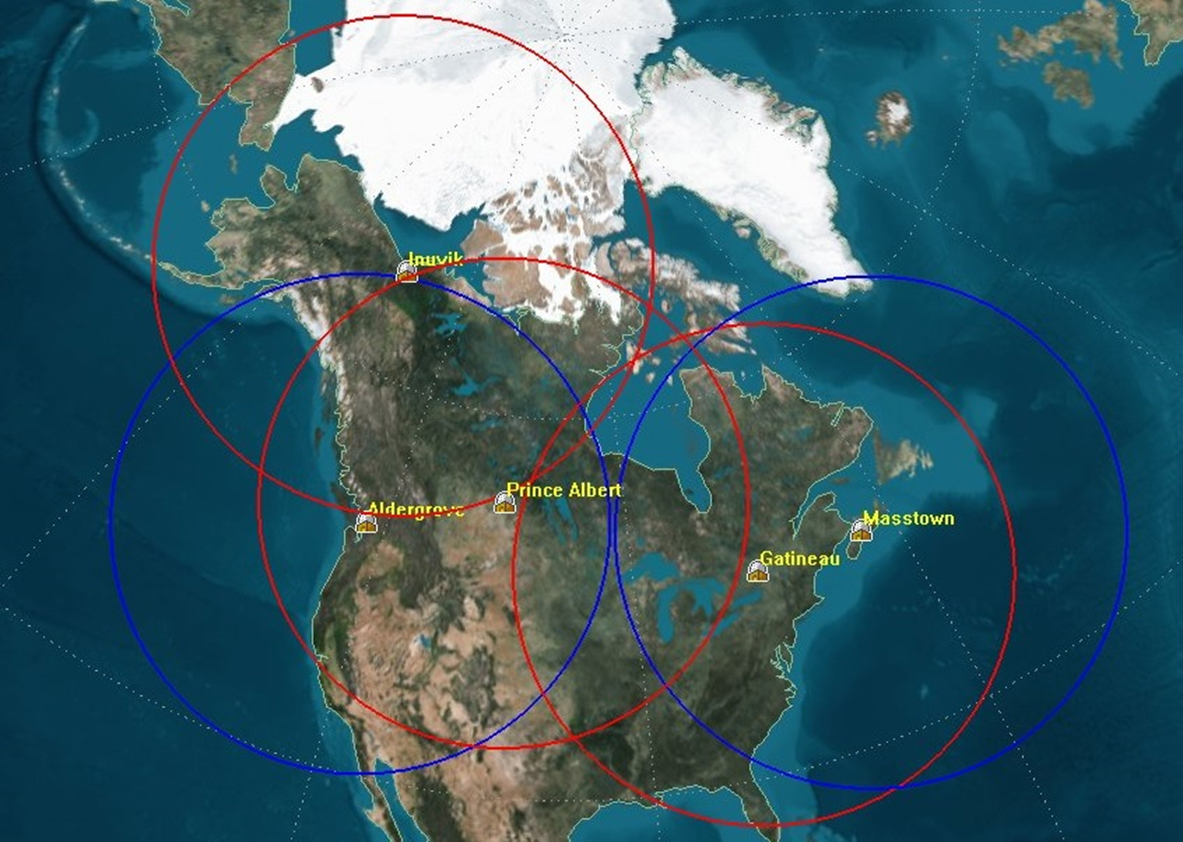

The Canadian military is looking now for a follow-on program for Sapphire. Called Surveillance of Space 2, the solution would allow Canada to continue providing information to the U.S. space surveillance network beyond 2021.

“Our thoughts right now are space-based, but our job is to look at all the options,” Frawley said.

Options could include a single satellite combined with a ground optical sensor or a constellation of electro-optical satellites. The system would track man-made objects in Earth’s orbits having altitudes of 6,000 kilometres or greater.

The Canadian military wants the new system to be able to detect dimmer objects — the focus will be on operational satellites, just a bit smaller than targeted currently. The number of observations the satellite could do per day to feed the Space Surveillance Network would also grow.

The preliminary cost estimate for the project ranges from $100-million to $249-million in Canadian dollars. The wide price range reflects the scope of options that might be considered.

Previously, there was talk about a 2021 launch date. But that is highly unlikely.

Sources say a contract could be signed in 2021 with the system going into orbit by 2025 or 2026.

“We’re fairly nascent in the program,” said Frawley. “It takes time to put things into space, but it’s an important mission for sure.”

Surveillance of Space 2 illustrates one of the big challenges with procurement of space assets, Frawley explained. Unlike an aircraft, ship or tank, the lifespan of a spacecraft is relatively short. “When you have a satellite that lasts between five and 10 years, it changes our mindset when it comes to how we procure these capabilities,” he said.

POLAR COMMUNICATIONS

At one point the Canadian government was looking at putting into orbit a constellation of satellites to provide communications for the Arctic as well as to gather weather data from the region. The launch date was tentatively scheduled for 2016 but the project, called the Polar Communications and Weather (PCW) Mission, has been scuttled.

“What we do have now is two separate projects,” Frawley explained. “One is called Tactical Narrowband Satellite Communication (TNS) Project. And there is a project that is still fairly nascent that we’re trying to move forward and it’s very important to us because of our focus on the Arctic. It’s called the Enhanced Satcom Program – Polar. That will give us the ability to do both narrowband and wideband over the North Pole specifically.”

Frawley said the military is hoping a draft solicitation for that project will be put out sometime in 2017.

“Obviously it will open for competition,” he said. “At the end of the day a company will propose a solution and we’ll go through the normal process on that. But the orbital mechanics say the only way you can cover off on the Arctic effectively would be probably multiple satellites given that you can’t use the geosynchronous orbit. You’ve got to have multiple satellites.”

RADARSAT CONSTELLATION MISSION

The RADARSAT Constellation Mission, or RCM, will be a follow-on program to the existing and highly successful RADARSAT-2 spacecraft. RCM, however, will provide more capability. Instead of a single satellite, RCM will use three radar-imaging satellites to conduct maritime and Arctic surveillance.

In January 2013, MDA Corp. was awarded a $706-million contract by the Canadian government that would see the Richmond company build, launch and provide initial operations for the RADARSAT Constellation Mission.

The first spacecraft is expected to be launched in the fall of 2018, Frawley noted.

He says the information to be gathered by the spacecraft will be critical for Canada’s warfighters. The Canadian military expects to use about 80 per cent of the data that RCM provides while the rest will go to other government departments, Frawley added.