(Volume 24-01)

By Tyler Hooper

A clinical study, which saw psychotherapy used in conjunction with the drug methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) to treat psychological and emotional trauma, wrapped up in Vancouver last November, and the results appear to be hopeful.

The study was led by several Vancouver-based psychotherapists who administered MDMA to six patients suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) to assist with psychotherapy sessions. Several of the patients are military veterans suffering from PTSD.

According to the Canadian Mental Health Association, PTSD “often involves exposure to trauma from single events that involve death or the threat of death or serious injury.” PTSD, through certain triggers such as sound or smell, often causes those who have witnessed trauma to relive the event. Those who suffer from PTSD often suffer from flashbacks, nightmares, have trouble sleeping and may become anxious, depressed and/or detached from their surroundings.

MDMA, commonly referred to as ecstasy (E), is labelled a psychoactive drug whose effects include increased sensations of empathy, euphoria and trust. The therapists who administered the drug to the clinical trial patients hoped the drug would allow the patients to open up more about their thoughts and feelings. Ultimately, the therapist ends up having a conversation with the person’s unconscious mind, which can be quite different from a regular conversation.

According to the therapists who administered the study, the drug increases the release of chemicals like serotonin, dopamine and hormones that, in theory, can relax patients, thereby allowing them to speak more freely about their thoughts and experiences.

Metro News reported that the patients were given 125mg of MDMA with eight hours of therapy. The patients also slept at the clinic and received additional counselling the following day; months later, they were given half the dose and more therapy.

The study was funded by the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) and a good portion of the funding for the study came from online donations from the MAPS website. It took Health Canada almost six years and $200,000 to approve the trial.

Mark Haden, chair on MAPS Canada’s Board of Directors and an adjunct professor at the UBC School of Population and Public Health, said that veterans often tend to be resistant to psychotherapy or talking in a group setting. Haden added that, “When you tell them that they don’t need to talk very much … that is quite attractive to veterans.”

Haden told Esprit de Corps, “To be honest with you, I was surprised of the level of welcome we got from the Canadian military. I sort of braced myself going into the military to talk about it … I really thought I would be challenged.” Haden added that while presenting to the Canadian military there seemed to be genuine interest shown towards the study.

In April of 2016, a psychiatrist from the Canadian Armed Forces told Global News that the military was not ruling out these sorts of alternative treatment, but the studies would need to published and proven to be safe.

MAPS is careful to suggest that laboratory-produced MDMA is not the same as street ecstasy, or “molly” as it is also known, because the street drugs are often laced with other chemicals and/or dangerous adulterants. “Pure MDMA has been proven sufficiently safe for human consumption when taken a limited number of times in moderate doses,” states the MAPS website.

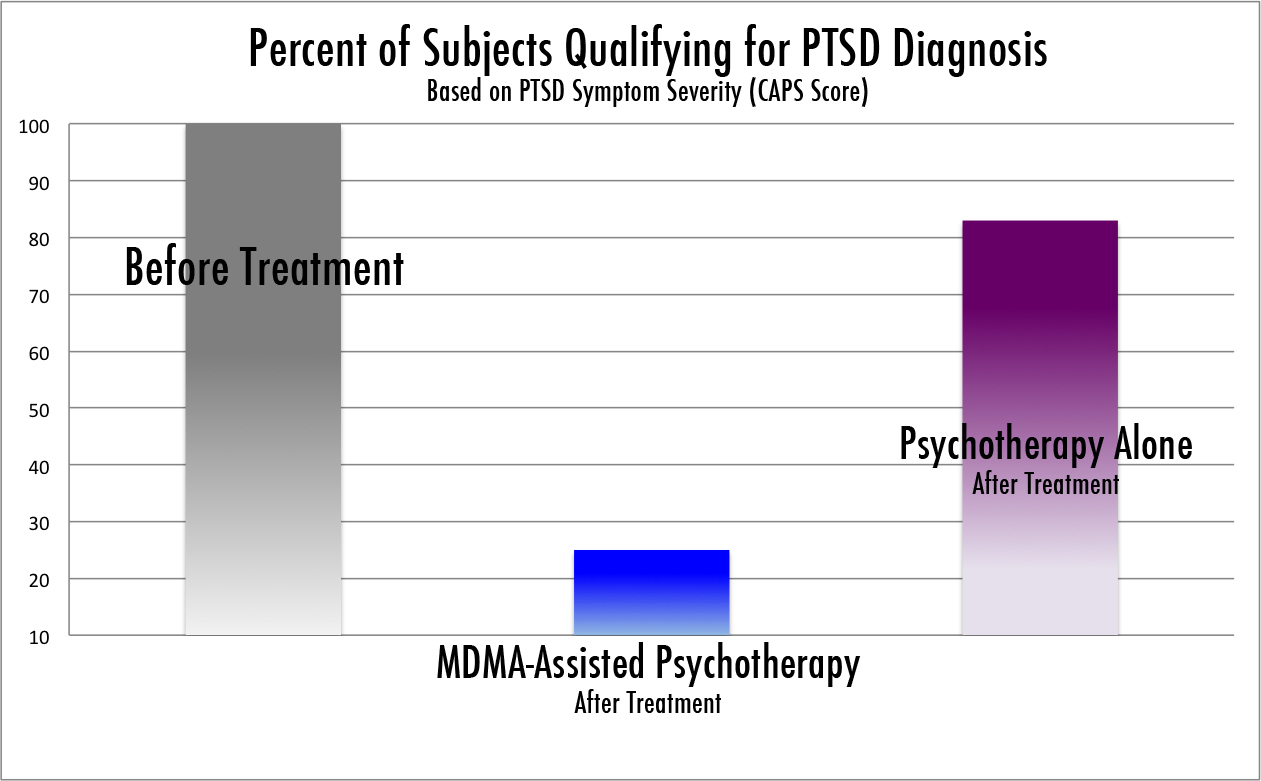

There will be another phase of research this spring with the hope getting the trial authorized as a legal prescription. Metro News reported that after the trial, 56 per cent of subjects no longer met criteria for PTSD. Followed up 12 months later, these same individuals now accounted for 66 per cent who no longer met the definition for PTSD. Two other recent trial studies, also involving the treatment of PTSD with MDMA in Charleston, South Carolina, also saw a 56 per cent decrease in the severity of PTSD symptoms.

According to the non-profit research and educational organization’s website, “MAPS is undertaking a roughly $25-million plan to make MDMA into a Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved prescription medicine by 2021.”

Since 2014, at least 54 Canadian veterans have committed suicide; however, the number could be higher due to lack of public reporting. Since the beginning of 2017, at least two Canadian military veterans have killed themselves, and both were thought to be suffering from PTSD.

Mark Haden said that during the study it was evident the veterans were in suffering due to trauma. “We know that it can be treated, and to watch this process happen in our society with the amount of suffering, and to know that this is available, is a source of great distress for us.”

Next month we’ll look at the study in more detail, and discuss alternative forms of treatment for veterans suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder.